China Must Scrap Draft NGO Law, Respect Freedom of Association

Comments Off on China Must Scrap Draft NGO Law, Respect Freedom of Association

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders – May 28, 2015) – The Chinese government must drop the draft Overseas NGO Management Law or remove proposed provisions that, as written, violate the fundamental human right to freedom of association and grant police vast powers to restrict civil society activism. Besides drastically restricting the operations of overseas non-profit organizations in China, the draft law targets domestic Chinese NGOs. Once enacted, it would deliver a “devastating” blow to independent Chinese groups, as the head of one Chinese NGO told CHRD.

“This draft law legitimizes the government’s systematic clampdown on freedom of association in President Xi’s ongoing war on civil society,” said Renee Xia, CHRD’s international director. “The real aim is strangling China’s independent groups by cutting off what has been their only source of support.”

Many Chinese activists are deeply afraid that the Ministry of Public Security and provincial public security departments are the authorities with the power to register overseas non-profit entities that intend to engage in any activities in China (Article 7). “This is a clear indication that the government treats the non-governmental sector as a threat to national security,” said one Chinese NGO staff. “For independent NGOs that depend on international support since the government has blocked all other channels of domestic support, we now face criminalization for associating with ‘overseas threats to national security,’ or we face being shut down due to drained funding sources.” (The names of Chinese activists who spoke to CHRD about the draft law are being withheld out of concern for their safety.)

There is a sense of trepidation of speaking out against the draft law, even as the government is soliciting public comments. The draft law is posted online for public consultation until June 4, after undergoing its second reading by the National People’s Congress (NPC) in April. However, it is likely to be adopted with few or no changes, as the NPC operates as a rubber-stamp legislative body for the Chinese Communist Party. Chinese NGO activists have told CHRD that few groups or individuals have so far made comments on the draft, since many have no faith in the independence of the process and also fear government retaliation. Some Chinese NGO activists worry that authorities would put them and their organizations under intense scrutiny if they express opinions on the draft, and that they would become the first victims under the law.

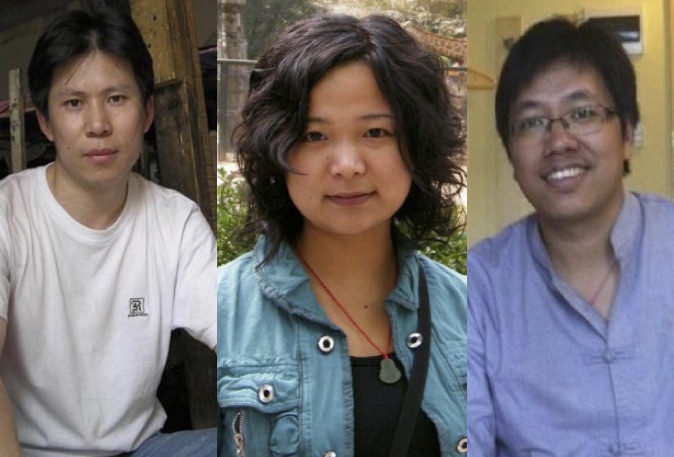

Xu Zhiyong (许志永), Wu Rongrong (武嵘嵘), and Guo Yushan (郭玉闪) have all been persecuted for their NGO activism. If China’s draft overseas NGO law is adopted, many others will face an uncertain future.

Over the past couple of years, the growing number of detained or imprisoned leaders from China’s civil society, along with more frequent police raids of NGO offices and investigations into groups’ finances, have exemplified the Xi government’s “zero tolerance” policy towards outspoken and independent Chinese groups. Some of the figures persecuted by the government include Xu Zhiyong (许志永), founder and director of Gong Meng (Open Constitution Initiative), Chang Boyang (常伯阳), co-founder and legal counsel for Zhengzhou Yirenping, Guo Yushan (郭玉闪), co-founder and former director of the Transition Institute, and Wu Rongrong (武嵘嵘), founder of Weizhiming Women’s Center.

A common pretext for police to conduct arrests and raids is that independent groups are suspected to have violated financial or tax regulations over funding received from either overseas or domestic donors. Following the arrest of Xu Zhiyong in August 2013, police also briefly detained and publicly humiliated on state media the financier Wang Gongquan (王功权), who made donations to Xu’s group, delivering a stern warning to private Chinese charities on funding independent or dissident groups. The draft law takes a step further: It bans Chinese individuals and non-profit organizations from receiving any funding from unregistered overseas NGOs (Article 38).

Article 38 also prohibits Chinese groups from conducting “activities” on behalf of or with the authorization of overseas NGOs (including those based in Hong Kong and Macau) that have not registered representative offices with the police or received a temporary “activity” permit issued by the police. The draft law’s broad definition of “overseas NGO” encompasses all international non-profits, including schools, hospitals, churches, charities, and sports clubs. Also, the law includes no clear definition of what constitutes a temporary “activity,” so the term could be interpreted to cover a range of behavior, from talking on the phone to checking emails on work-related matters. The lack of clear legal definitions would permit police to exploit arbitrary powers to closely monitor overseas NGOs and approve NGO “activities.” It also hands police a tool to target independent, outspoken Chinese groups and subject their leaders to persecution.

Under the draft law, domestic organizations that engage in any “activities” or accept funds from an overseas NGO that is un-registered or un-approved by the police would face closure and a fine of 50,000 RMB (US $8,000), and their staff members could be administratively detained (Article 58). Many international non-profits will be unable—or unwilling—to register or get approval for holding “activities,” as they may find the registration or approval process too burdensome and invasive.

The draft law not only bans non-registered overseas groups from funding any Chinese individual or organization (Article 6), but also prohibits registered overseas NGOs from funding for-profit organizations (Article 5). Such a legal provision would cut off funding for independent non-profit Chinese groups that have been forced to register as businesses or for-profit firms. The process to register as a domestic non-profit organization requires Chinese groups to obtain sponsorship from a government entity. In order to maintain their independence, some Chinese organizations—like those that voice dissident views or challenge government policies on health rights, women’s rights, legal and social reform, discriminatory practices, or labor rights—have not met the requirement for official sponsorship, or have not wanted to subject themselves to direct government supervision. Such groups, including the HIV/AIDS education organization Beijing Aizhixing Institute, as well as Gong Meng, the Transition Institute, and the Beijing Yirenping Center, have had no choice but to register as for-profit entities.

The draft law also includes many provisions that would facilitate police monitoring and surveillance. For instance, half of the registered overseas NGO’s personnel would be required to be Chinese nationals recruited from a government-approved agency, and their personal information must be reported to the police (Article 32). These restrictions subject any Chinese citizens working for overseas NGOs to police harassment and intimidation. It also opens the door for police to install their undercover agents in such organizations, or force Chinese staff at NGOs to report on their “activities,” which has for years been a routine police tactic aimed at monitoring international and domestic NGOs.

Restrictions on overseas funding for Chinese NGOs constitute a violation of the right to freedom of association, as protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, which China signed but has not ratified). The UN treaty body monitoring the implementation of ICCPR has declared that constraints on such support are considered a violation of Article 22 of the Convention. Treaties that China has signed and ratified, such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, also protect freedom of association. Other treaty bodies that have expressed concern about government restrictions on NGO funding include the Committee against Torture, Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child.

In March, an NPC spokesperson said the law was needed “for safeguarding national security and maintaining social stability.” There is no coincidence that the government is pushing for the overseas NGO draft law at the same time as it puts forward two other draft laws, on national security and counter-terrorism. The UN’s special expert on freedom of peaceful assembly and association has made clear that many justifications made by UN Member States for putting constraints on NGO funding sources in the name of “national security” or “counter-terrorism” are illegitimate, and that the restrictions allowed for under human rights treaties should never be used as a “pretext to constrain dissenting views or independent civil society.”

“What is particularly alarming is how the government wants to write into law its long-standing hostility to civil society,” says Renee Xia. “This draft law basically says that current Chinese leaders want to link NGOs and civil society activism directly to national security and terrorist threats.”

CHRD calls on the Chinese government to drop or substantially revise the Overseas NGO Management Law to bring it into line with international human rights standards. The draft law’s current form legitimizes the government’s ongoing violation of the right to freedom of association and its increased criminalization of civil society leaders. In particular, any meaningful revision must include removal of the authority to manage NGOs from the hands of the public security organs, and the removal of funding restrictions in order to allow Chinese NGOs to receive support from both domestic and overseas sources.

Contacts:

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 240 374 8937, reneexia@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Research Coordinator (English), +1 209 643 0539, victorclemens@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083, franceseve@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD

Follow CHRD on Twitter: @CHRDnet